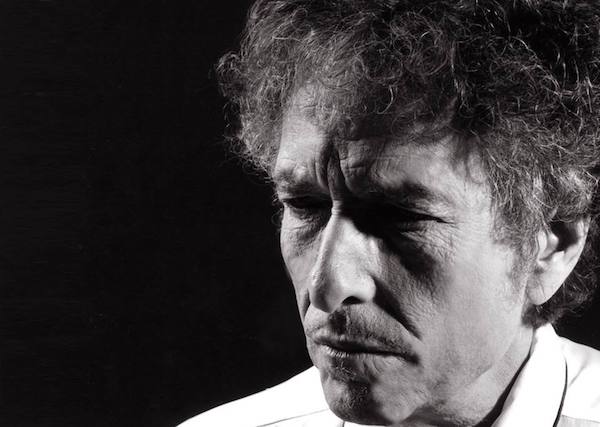

Interview with Bob Dylan

Daily / Musica / Interview - 01 January 2019

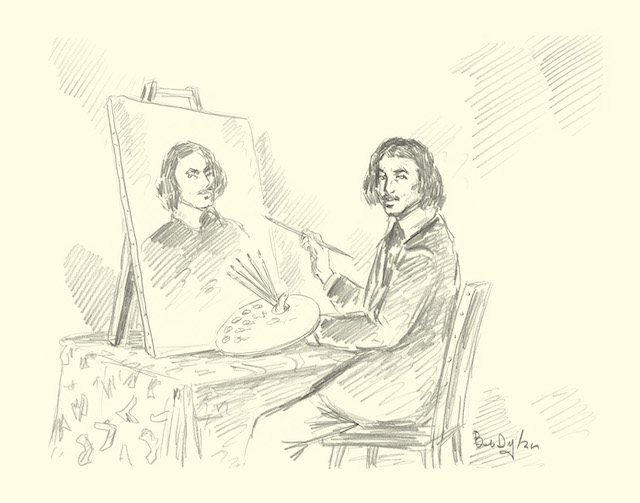

Bob Dylan - Mondo Scripto is the exhibition at the Halcyon Gallery in London.

Bob Dylan - Mondo Scripto is the exhibition that was held at the Halcyon Gallery in London. It presented the hand-written lyrics of the most famous songs of the artist, singer-songwriter and Nobel prize-winner: each one accompanied by an original pencil drawing.

Mostly after hours. Summer evenings, winter evenings. Usually one a week, sometimes three or four.

Q. Was writing out the songs difficult?

A. In the beginning it was, because I tended to race ahead of myself. I’d skip verses, that kind of thing.

Q. Did it take some time to figure out how they’d be organised on paper?

A. It did, because the songs vary in length.

Q. Did writing the songs out cause you to reflect on the process of songwriting?

A. Yeah in a way, but then again there is no one certain process that works for everything. Once you’ve recorded the song, you forget the steps it took to get there.

Q. What makes a good song? What makes a bad song?

A. A good song connects with people on a personal level. A bad song doesn’t reach anybody.

Q. Some of these songs are over 50 years old. Did you remember all of them? Were there songs here that you didn’t remember writing?

A. 50 years old isn’t that old. Maybe to someone who’s in their twenties, but not to someone who is in their eighties. The song ‘Barbara Allen’ is three or four hundred years old and we are still singing it. But sure, there are a lot I don’t recall writing. I mean I know I wrote them, but I can’t say where or when.

Q. Did you see any of these songs and think, ‘Hey, I should start performing that one again live’?

A. ‘Song To Woody’ – I haven’t done that in ages. I think maybe that one. There may be one or two others as well.

Q. Did you look at any of these songs and think, ‘I should STOP performing that one’?

A. There are some songs with verses here and there that could be dropped or changed, but not entire songs.

A. Yeah, totally consciously. In Mary Jo Bang’s translation of Dante’s Inferno, there are corresponding drawings by Henrik Drescher and they are very realistic and literal, and I took that as a guide. There’s others as well. The Reginald Marsh drawings for John Dos Passos’ USA Trilogy were a big influence.

Q. Do you think that an illustration can get in the way of someone’s interpretation of a song?

A. It probably could. But videos have already done that.

A. The ones that are more visual do.

Q. Some of the illustrations are quite graphic, almost troubling – like the man with his tongue bleeding in ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’, and the man drowning in ‘The Times They Are A-Changin’’. Why those songs for such graphic images?

A. Those images come straight from the songs. They fit the songs. Did you ever see Otto Dix’s drawings of the scenes from World War I? They’re beyond graphic. Mine are tame compared to those.

At first it was a bit of a dilemma, but then I started experimenting with other people’s songs. The Tom Petty song ‘Love is a Long Road’ – I drew a picture of a dirt road. For the Billy Joel song ‘Moving Out’ I drew a picture of a moving van. The Prince song ‘Darling Nikki’ – I drew a picture of a young girl masturbating in a hotel lobby. I saw that, okay, it can be done, so then I did it with my songs.

Q. Did you ever find the illustrations changed the meaning of the song for you?

A. The meaning of the song is in the hearing of it. Songs can change their meaning depending on who is singing. When the Grateful Dead do ‘Big River’ it means something different than when Johnny sings it.

A. There wasn’t time for that really. Not only that, it’s just not practical. A song is really a form of storytelling that changes from minute to minute, and adapts itself to different circumstances. A painting is a fixed scene, where something is nailed down and made permanent. You can’t leave holes in the centre. With songs you can do that. I wouldn’t mix the two or try to force them together, because they have nothing in common.

Q. Who are some artists whose drawings you admire?

A. Rembrandt, especially his drawings of St Alban’s Cathedral. Albrecht Dürer’s Knight, Death and the Devil, Rubens, Charles Le Brun. I like van Gogh’s drawings as well.

Q. Who are some lyricists whose lyrics you admire?

A. A lot of them. Hank Williams, Johnny Mercer, Merle Haggard.

Q. What makes a good drawing?

A. The right lines in the right places.

Q. What makes a good lyric?

A. The right words inside of the right melody.

We thank the Halcyon Gallery for the courtesy.

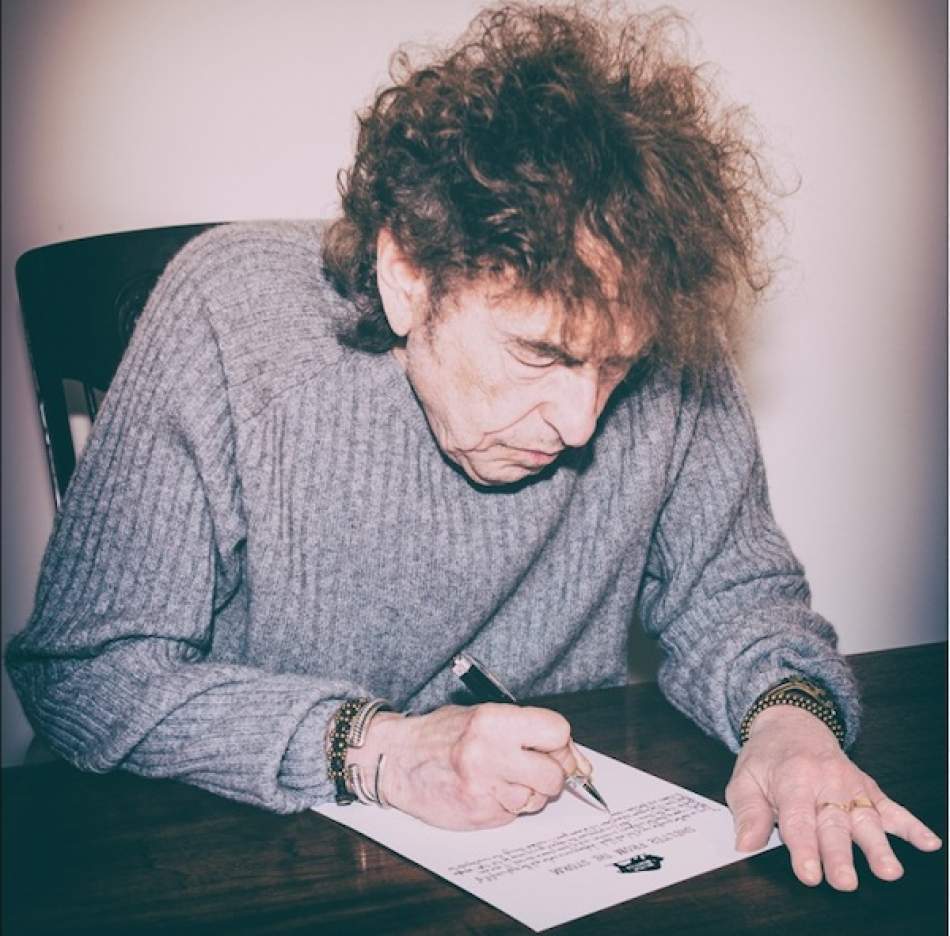

Q. When did you find the time to write out all those songs?

Mostly after hours. Summer evenings, winter evenings. Usually one a week, sometimes three or four.

Q. Was writing out the songs difficult?

Look at the Gallery: Bob Dylan - Mondo Scripto, the exhibition

A. In the beginning it was, because I tended to race ahead of myself. I’d skip verses, that kind of thing.

Q. Did it take some time to figure out how they’d be organised on paper?

A. It did, because the songs vary in length.

Q. Did writing the songs out cause you to reflect on the process of songwriting?

A. Yeah in a way, but then again there is no one certain process that works for everything. Once you’ve recorded the song, you forget the steps it took to get there.

Q. What makes a good song? What makes a bad song?

A. A good song connects with people on a personal level. A bad song doesn’t reach anybody.

Q. Some of these songs are over 50 years old. Did you remember all of them? Were there songs here that you didn’t remember writing?

A. 50 years old isn’t that old. Maybe to someone who’s in their twenties, but not to someone who is in their eighties. The song ‘Barbara Allen’ is three or four hundred years old and we are still singing it. But sure, there are a lot I don’t recall writing. I mean I know I wrote them, but I can’t say where or when.

Q. Did you see any of these songs and think, ‘Hey, I should start performing that one again live’?

A. ‘Song To Woody’ – I haven’t done that in ages. I think maybe that one. There may be one or two others as well.

Q. Did you look at any of these songs and think, ‘I should STOP performing that one’?

A. There are some songs with verses here and there that could be dropped or changed, but not entire songs.

Q. Most of the illustrations seem to be very literal. Was this something you did consciously?

A. Yeah, totally consciously. In Mary Jo Bang’s translation of Dante’s Inferno, there are corresponding drawings by Henrik Drescher and they are very realistic and literal, and I took that as a guide. There’s others as well. The Reginald Marsh drawings for John Dos Passos’ USA Trilogy were a big influence.

Q. Do you think that an illustration can get in the way of someone’s interpretation of a song?

A. It probably could. But videos have already done that.

Q. Do some songs lend themselves more easily to illustration than others?

A. The ones that are more visual do.

Q. Some of the illustrations are quite graphic, almost troubling – like the man with his tongue bleeding in ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’, and the man drowning in ‘The Times They Are A-Changin’’. Why those songs for such graphic images?

A. Those images come straight from the songs. They fit the songs. Did you ever see Otto Dix’s drawings of the scenes from World War I? They’re beyond graphic. Mine are tame compared to those.

Q. Was it difficult to come up with concepts for illustrations?

At first it was a bit of a dilemma, but then I started experimenting with other people’s songs. The Tom Petty song ‘Love is a Long Road’ – I drew a picture of a dirt road. For the Billy Joel song ‘Moving Out’ I drew a picture of a moving van. The Prince song ‘Darling Nikki’ – I drew a picture of a young girl masturbating in a hotel lobby. I saw that, okay, it can be done, so then I did it with my songs.

A few were a bit of a puzzle. ‘Tangled Up In Blue’ – I remember when I wrote that there were a lot of albums with blue in the title. Joni Mitchell’s ‘Blue’, Coltrane’s ‘Blue Train’, Miles Davis’ ‘Kind of Blue’, ‘Blue Hawaii’, ‘Blue Bayou’, ‘Blue Moon of Kentucky’, ‘Call Me Mr. Blue’ – the colour blue seemed to be everywhere. I felt like I was being swamped in it ... or tangled up in it, to be more precise. A concept like that was hard to get a fix on. At the end of the day, I went mainly with the song titles, and maybe the first line.

Q. Did you ever find the illustrations changed the meaning of the song for you?

A. The meaning of the song is in the hearing of it. Songs can change their meaning depending on who is singing. When the Grateful Dead do ‘Big River’ it means something different than when Johnny sings it.

Q. Did you ever consider doing paintings for each of the songs instead of drawings?

A. There wasn’t time for that really. Not only that, it’s just not practical. A song is really a form of storytelling that changes from minute to minute, and adapts itself to different circumstances. A painting is a fixed scene, where something is nailed down and made permanent. You can’t leave holes in the centre. With songs you can do that. I wouldn’t mix the two or try to force them together, because they have nothing in common.

Q. Who are some artists whose drawings you admire?

A. Rembrandt, especially his drawings of St Alban’s Cathedral. Albrecht Dürer’s Knight, Death and the Devil, Rubens, Charles Le Brun. I like van Gogh’s drawings as well.

Q. Who are some lyricists whose lyrics you admire?

A. A lot of them. Hank Williams, Johnny Mercer, Merle Haggard.

Q. What makes a good drawing?

A. The right lines in the right places.

Q. What makes a good lyric?

A. The right words inside of the right melody.

We thank the Halcyon Gallery for the courtesy.

© All right Reserved