New Italian Migrations to the United States, interview with Laura E. Ruberto and Joseph Sciorra

Daily / Interview - 25 March 2019

The two books analyze the Italian immigration.

Scholars Laura E. Ruberto and Joseph Sciorra edited New Italian Migrations to the United States, a two-volume collection that explores Italian immigration to the United States from 1945 to the present day.

Q. Did Italian Americans mobilize against these restrictions?

A. These restrictions stayed in effect until 1965. Importantly, Italian Americans—most whose family had first come to the United States before that law went into effect—helped remove the quota system. In the two decades following the end of World War II, Italian Americans worked with other groups on both sides of the Atlantic to help activate a change in the immigration laws in the United States, most notably through the American Committee on Italian Migration (ACIM), founded in 1952 expressly to eliminate the national quota system and aid Italian exit and entrance processes in light of Italy’s postwar crisis.

A. We propose the term “rebooting” to explain this phenomenon –that each new wave of immigrants recharged or rebooted Italian American culture in exciting and dynamic ways.

Q. We know about the history of Italian immigration in the early twentieth-century, the era of Ellis Island. But what is important about the last seventy years of immigration to the United States—the era you cover in your books?

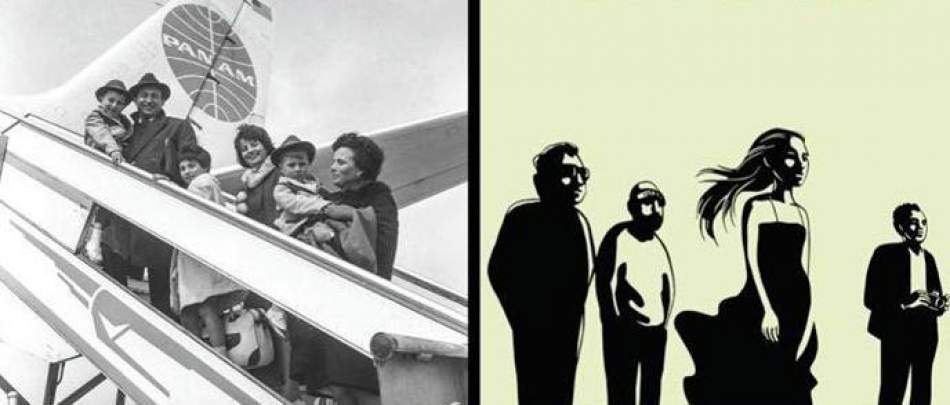

A. In order to understand the importance of our volumes, readers have to consider some of the conventional images they probably associate with Italian migration—black and white photographs, for instance, of peasant families staged near transatlantic ships. Our two volumes, and all our contributors’ research within them, counter such images by telling the story of Italian migration to the United States over the last seventy years.

Look at the Gallery: New Italian Migrations to the United States

Most scholarship as well as popular culture that covers Italian American history assumes that Italian migration started in the late-nineteenth-century and basically concluded by World War II. This impactful wave of migration also usually gets talked about with a straight-forward, linear narrative of arrival—acclimation—assimilation from immigrant to third generation.

There are lots of reasons why this standard story makes sense—most significantly perhaps is that the simple fact that the number of Italians who have immigrated to the United States since 1945 is but a fraction of the number who immigrated at the turn of the twentieth century. Those early immigrants, numbering over four million, have participated in and influenced all aspects of U.S. society.

And yet, the experiences, the stories, and the cultural outpouring of post-World War II immigrants and their descendants have usually been enveloped by the preexisting models for understanding Italian American identity or otherwise been erased.

Q. What struck you most about Italian immigration of the 1950s?

A. The period of immigration in the 1950s was mostly one we refer to as a “working class” wave that was closely tied to the pre-established Italian American community. This wave emigrated mainly from southern Italian regions, arriving often with a skill or trade and remaining in the skilled labor force in the United States. At the same time, this wave of migrants entered the middle class more quickly than their pre- World War II counterparts.

Importantly, Italian migration was still legally restricted in this era and the laws permitting migration to the United States was tightly connected to the pre-existing Italian American communities. In other words, many of the immigrants who arrived in the 1950s were able to obtain permission to do so because they had family already living in the United States—what is commonly called chain migration—and because they were greatly aided by Italian American activists working towards immigration reform.

A number of the essays in the two collections focus precisely on this era as well as on the wave of immigration that came after the 1950s. Beginning in the 1970s and continuing today, a more educated class of Italians began arriving and settling in the United States. The “elite” group of migrants—a group who, still today, generally doesn’t even consider themselves immigrants—has not always engaged with the pre-established Italian American communities but at times, we and our contributors have noted, important connections have been made between the different waves.

Q. Have there been any immigration restrictions on Italians?

Italians have never been explicitly singled-out as a group barred from entering to the United States, as for instance happened with the series of Chinese-exclusion acts that barred Chinese immigrants. However, Italians, along with people from many countries were discriminated against with the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act. This law created a restricted limitation on migration by creating a national quota system calculated in a way that quite explicitly discriminated against Southern Europeans (and others). The quota for Italians limited migration to just 3,845 people a year.

Q. Did Italian Americans mobilize against these restrictions?

A. These restrictions stayed in effect until 1965. Importantly, Italian Americans—most whose family had first come to the United States before that law went into effect—helped remove the quota system. In the two decades following the end of World War II, Italian Americans worked with other groups on both sides of the Atlantic to help activate a change in the immigration laws in the United States, most notably through the American Committee on Italian Migration (ACIM), founded in 1952 expressly to eliminate the national quota system and aid Italian exit and entrance processes in light of Italy’s postwar crisis.

In 1965, the Immigration and Naturalization Act was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson—this drastically altered how the United States regulated immigration, opening up the borders to more immigrants from Italy but also to many other parts of the world. Today the conversation (and controversies) around immigration in the United States is mostly about people coming from outside of Europe but many of the laws that are currently being disputed went into effect to help Italian and other European immigration.

Authors in our Volume One in particular take up the histories of the development of the 1965 law, through careful politicking in both the United States and Italy.

Q. What are some of the ways Italian immigration of the last seventy years have shaped culture?

A. Oh, there are so many ways! We take this on in both volumes but especially in Volume Two. In fact, we argue that it was not only people who emigrated to the United States but an Italian style too. Today we might refer to this as the “Made in Italy” brand but it was first noticeable through the importation of fashion, design, food, entertainment, and other habits of everyday life and continues today to inform how Italian Americans from any generation defines themselves and is defined by others.

Italian style is noticeable in imported commodities (from Moka coffeemakers to FIATs) but also in those individuals who embodied the new cultural cachet of Italy (Sophia Loren, Luciano Pavarotti, Mario Andretti, and so forth). In our more contemporary moment we see this kind of Italian style in a number of ways—from the importation of everything from the Slow Food movement to leading science and technology professionals.

And it wasn’t just an imported style that effected change, there were other, more everyday ways that the influx of new immigrants influenced the culture too.

Q. Some of the essays of New Italian Migrations to the United States talk of the arrival of new waves of Italian immigrants and their insertion into the pre-established communities of Italian Americans. What effect did new immigrants have on pre-established communities of Italian Americans?

A. We propose the term “rebooting” to explain this phenomenon –that each new wave of immigrants recharged or rebooted Italian American culture in exciting and dynamic ways.

The issue of “Italian style” and how that influenced consumer culture is related here as well. But it’s more than that. A number of our contributors talk about this issue—with respect to, for instance, popular and consumer culture (e.g., Guido youth culture), with respect to folk dance traditions, and with respect to foodways/food culture. In addition, Italian immigrants influenced local culture, through their involvement in the celebrations of, for instance, religious feast days among Italian American communities and Catholic parishes.

Laura E. Ruberto is a professor of Humanities at Berkeley City College. Joseph Sciorra is the Director for Academic and Cultural Programs at City University of New York. New Italian Migrations to the United States Vol. 1 and Vol. 2: Art and Culture since 1945 both published by the University of Illinois Press in 2017.

© All right Reserved